Legend, not historical record, behind a name

Liam Alastair Crouse discovered recordings on the Tobar an Dualchais website which show the folklore that shaped place and place names in the Hebrides…

Am Baile, the main village in Eriskay, is bordered on its eastern flank by a small, undulating dell that climbs gently up from the harbour of Na Hann to the foot of the Beinn Sgrithean hill grazing.

This feature is Glaic a’ Chòmhraig, the Glade of the Battle. But who fought here, why, and when, are matters of dispute between the various stories describing the battle.

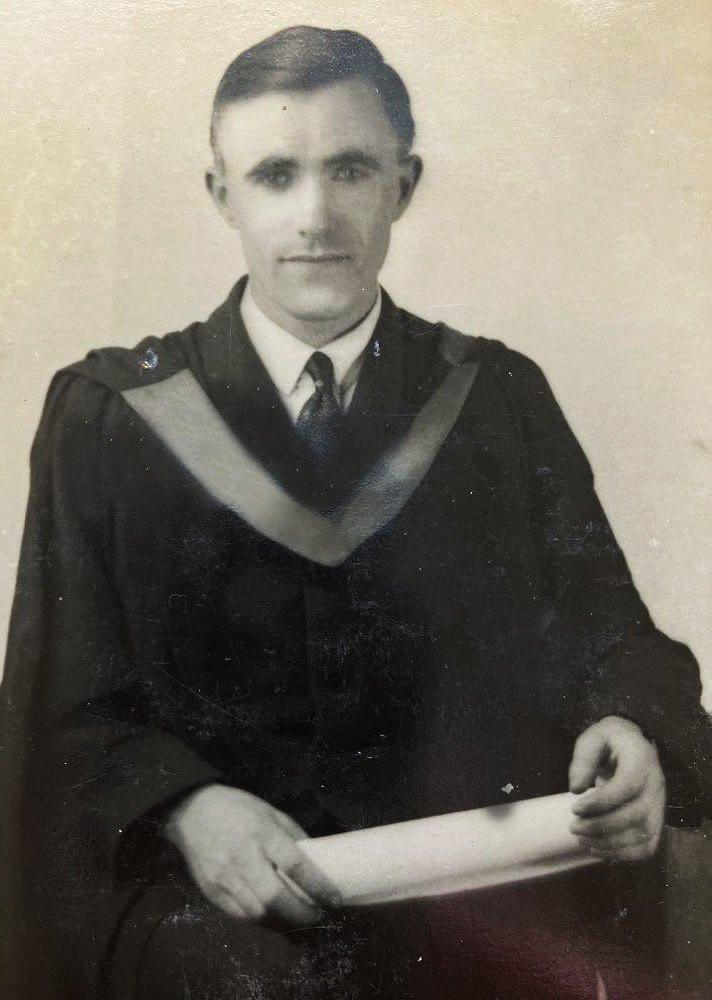

The earliest source for this placename is perhaps Dòmhnall Eachainn Dòmhnallach, Donald MacDonald of Eriskay. Beside his position as schoolmaster, he was also a poet, folklorist, and Gaelic scholar of considerable skill.

As a student home for the summer, he made a valuable collection of oral material from the island in 1933 at the behest of James Delargy, the founder of the Irish Folklore Institute. The collection is part of the manuscript collection of the National Folklore Collection at University College Dublin.

Among the supernatural stories and accounts of daily life, he recorded 16 place names and their associated folklore.

Glaic na Còmhraig – the spelling varies according to informant – was the site of a bloody fight between a group from the north end of the island versus the southern end over rights to peat cutting. One side was massacred and buried at the spot.

After many years heavy rains exposed the buried remains and the site became known as Lag nan Cnàmh, or the Hollow of the Bones.

Donald’s account points to the social conflicts which may have developed following the clearance to Eriskay of people from South Uist, Fuday, and even Skye.

The population of this small island of nearly three square miles rapidly swelled to over 400 souls by the middle of the 19th century.

The new communities may have been settled at first according to familial and geographical relations, which resulted in the north-south divide suggested by the narrative.

The crowding of disparate factions could at times give rise to spats over the control of finite resources such as peat. In the Napier Commission accounts, for example, we read that by 1883 the peats were “well-nigh exhausted altogether” and could have led to increased tensions within the community.

The second description of a battle at Glaic a’ Chòmhraig – the version used by this informant – was collected in 1953 by Calum Maclean from Dòmhnall MacAonghais, Donald MacInnes originally from Eriskay and resident in South Glendale (track ID 2221).

He describes a skirmish between two great clan heroes, Iain Mùideart, or John of Moidart, and Dòmhnall mac Iain ’ic Sheumais, or Donald of Eriskay, who both laid claim to Eriskay.

John of Moidart landed his force, possibly at Na Hann, but were met by a superior force. Nearly all the invading force, including John of Moidart, were slain. Another tradition in the island says that the dead were buried under the cairns at the top of the glade, which can still be seen and are marked on the OS maps.

It is not altogether clear which John of Moidart the story suggests.

The first, and most celebrated, John died in 1584, probably in Caisteal Tioram.

The second John, the grandson of the first, did indeed die in Eriskay, in 1670. However neither individual was a contemporary of Donald of Eriskay (1570-1630), whose name is most recognised today as the hero of the Battle of Carinish in 1601 and subject of the waulking song bearing his name, “A Mhic Iain ’ic Sheumais”.(TAD ID 106904)

There is also a possibility that another Moidart became enmeshed within the tradition. Donald of Moidart, a contemporary of Donald of Eriskay, seized the lands of Boisdale from Clan MacNeil at the start of the 17th century.

Is it possible that he landed in Eriskay as part of his campaign and his name confused with his close relations?

Whatever the reality, oral tradition is depicting the Isle of Eriskay during Linn nan Creach, The Age of the Forays, as lying on a fault line of clan conflict between the MacNeills in Barra, Clanranald in South Uist and Moidart, and Clann Ùisdein, the MacDonalds of Sleat, who held dominion over Trotternish and North Uist.

It is no surprise that clan battles would feature within the island’s folklore.

The last account of Glaic a’ Chòmhraig is to be found in a pamphlet produced by schoolchildren of Eriskay School in 2006.

They collected 19 place names and their associated lore, mostly in and around Am Baile, where the now-closed school is located.

Here the battle is a Viking one, ascribed to the 8th or 9th century. Folklore regarding the Norse in this area are common, such as those tales about the Isle of Fuday (track ID 2083 & 2070), so there could be a seed of truth within the account.

Battles involving the Norse appear elsewhere in local folk tradition, such as the battle at Loch nan Arm between Triùiribheinn and Stulabhal, described by Fr Allan Mcdonald (CW58 EUL), although granted they usually suffer defeat at the hands of the islanders.

Whichever of these three stories is true is anyone’s guess.

Folklore is not historical evidence, strictly speaking. It often tells us more about the person telling the tale, and their world, than the world in which it is set.

Rather than searching for the historical truth behind the placename, I’d like to discuss what these stories teach us about how the Gaelic oral tradition functions.

Firstly, they demonstrate just how variable the oral tradition can be.

Multiple legends and stories can coexist with each other in a community to explain or describe the same thing, such as a place name, in different – and even conflicting – ways.

These three distinct stories, related only by their setting of Glaic a’ Chòmhraig, belong to wholly different time periods.

Each teller may choose the story which best matches their own experiences, worldview, sources, or preference.

Indeed, if we look at the dates of the sources, the more recent the source, the older the period in which they are set.

This is a curious aspect of folklore, which may be connected to legendary creation. The older a story’s setting, the more difficult it may be to disprove it.

Considered in another way, the stories’ setting may reflect the gradual easing of community tensions from the mid-19th century onwards.

The themes turn from internal dispute, to external threat, to collective past. But maybe that’s reading too much into what is a sparse and disparate record.

What it does show, however, are the difficulties inherent in taking folklore as historical fact.

Placename folklore can be just as variable as other forms of folklore, and we should tread with care.